Ephemera: Mary Ann Murray – a Housemaid from Dunkeld @ Hampton Hall, Malpas

The Book

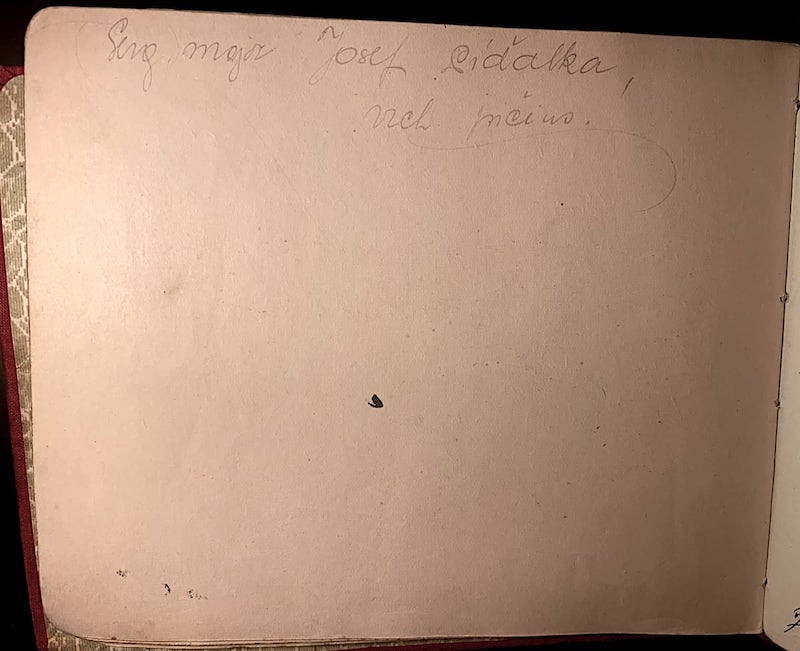

For the second entry in this series, I have chosen to add an autograph book which, in some regards, is a very typical example — containing poems, memes, toasts, and quite a few pictures of Union Jack flags. On closer inspection, however, it becomes a mystery starting with a distinct lack of personification. Typically, on the inside cover or opening page of an autograph book is an inscription or dedication giving a clue to the book's owner — alas, this book contains none. Additionally, only one entry out of 91 made between (where identifiable) 25 December 1917 and 12 August 1921 contains a 'to' — an entry from a Private John Baker, on an unspecified date, which contains 'To Mary'. The majority of entries use the format '@Hampton Hall, Malpas /content / by / from' — suggesting the focus of the book is the place not the individual.

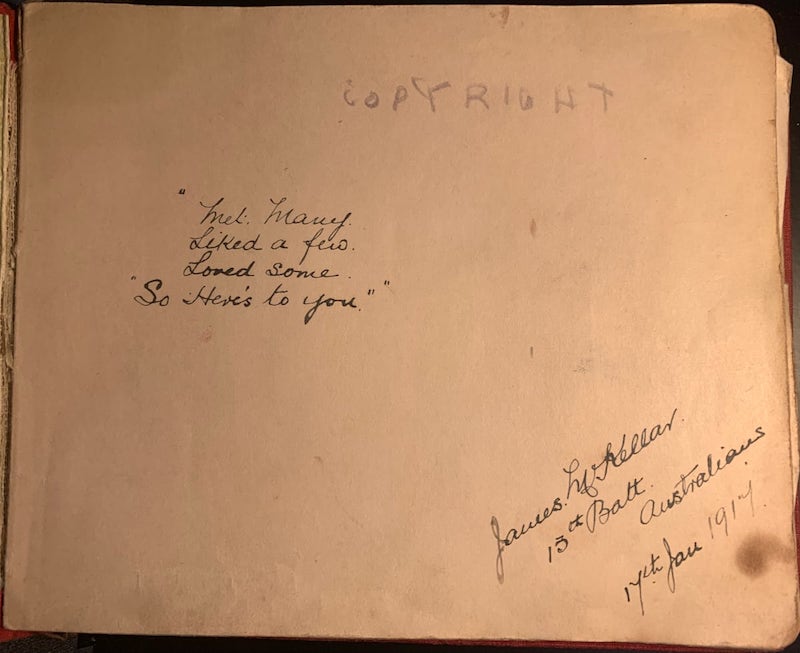

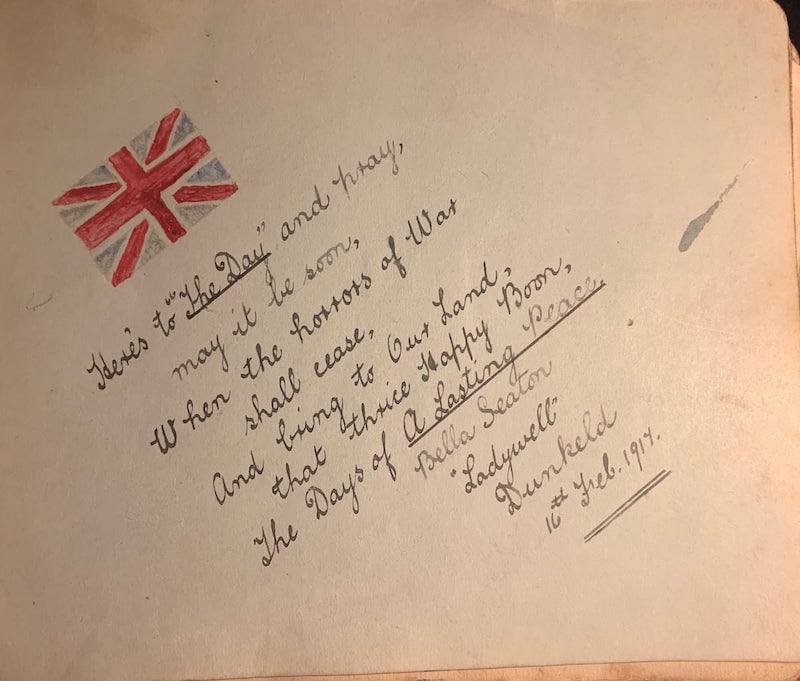

The book was among the first I purchased, and my initial thoughts were that it was related to a convalescent home based on the following: there are a number of soldiers listed in the book and the first entry to (physically) appear in the book is from a James Mackellar, 13th Battalion, Australian Imperial Force — originally from Drummond, Scotland — who was wounded in August 1915 on the Gallipoli peninsular. He was discharged to England in October of that year and would remain until July 1916, before heading back to Australia for home service.1 Another entry is from an unidentified Gunner Schofield who signs his name with, 'Wounded at Arras April 16th'. Further evidence in support of the convalescent setting: there was a Red Cross Hospital in Malpas — Mrs Wilding Jones (see below) of Hampton Hall was one of its supporters, and there was another auxiliary hospital nearby at Higgins Hill House — where Miss Wilding Jones volunteered as a cook.2 As well as including serviceman, the book also featured a number of entries from young women around the ages of 19-20, and there are several entries that you would expect to find in a nurse's book. There is an entry from a relative (Jessie M. Mackellar, James's Sister), a few waving flags, a bit of propaganda, and an 'In memoriam' entry. However, the lack of personification steers me away from the convalescent idea as well, as the book contains entries from soldiers who I can find no account of being wounded. There is also no record — that I have found — of Hampton Hall being used in such a manner.

Mary Ann Murray and Dunkeld

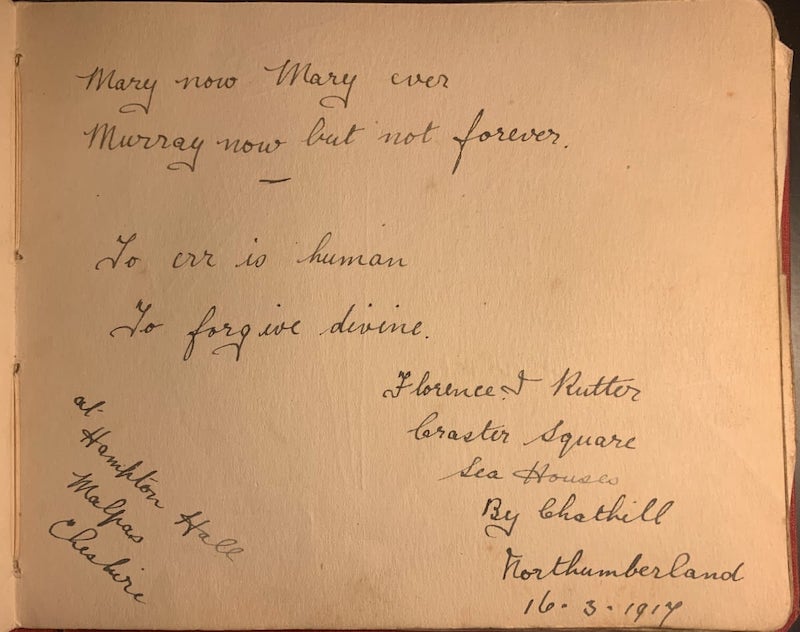

From my research, I believe the book once belonged to Mary Ann Murray (1899-1975) from Dunkeld. Following the 'To Mary' entry, there is this entry from a Florence Rutter (Figure 2), from Northumberland, which provides the surname. (I should admit, I mis-transcribed 'Murray' as 'marry' first time around, but I came to the same conclusion via a slightly longer route).

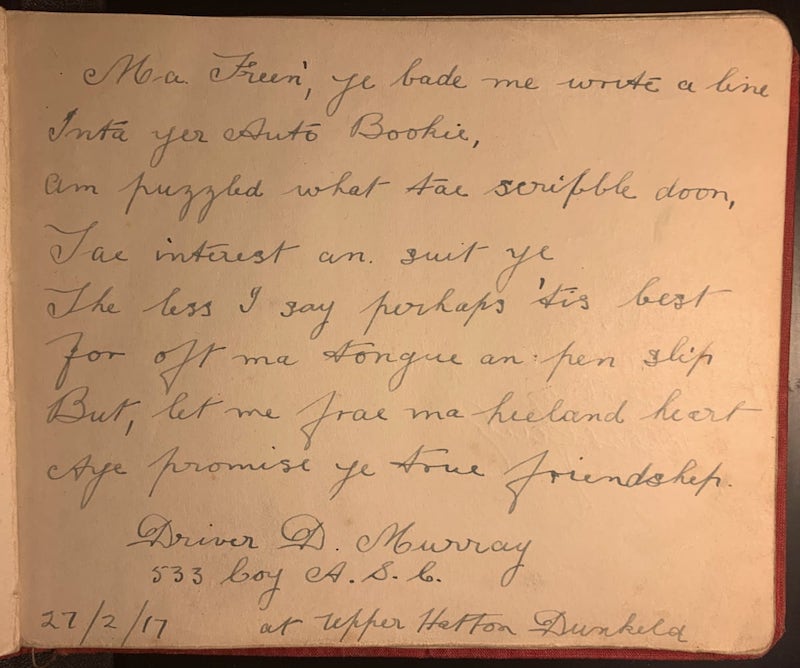

Next, while most of the entries are @Hampton Hall there is an exception. Around the end of February 1917 and early March 1917, it appears Mary travelled back to Dunkeld and there are many entries from this area — including a number of entries from the Murray family.

These entries include: Duncan, Gregor, Katie, Margaret Scott, and Helen. According to the census records they all resided at Upper Hatton. The household was made up of Peter Murray (1860-1943) — a coach builder, who was married to Maggie Murray (1871-1907) — they had nine children: Duncan (1891-1918), Margaret Scott (1893-1979), John (1898-????), Jane (1899-????), Mary Ann (1900-1975), Hellen (1901-1925),Gregor (1901-1967), Catherine (Katie) (1905-????), and Peter (1907-1907). The records are hazy, but Peter died a few months after being born and I cannot find any records, except for birth, for John and Jane, who I expect may also be infant deaths. Of the remaining six children, five left their signatures in the book leaving only Mary Ann Murray missing — which makes sense if she was the book's owner.

I have one further clue as to who Mary was, but I first want to talk briefly about Dunkeld.

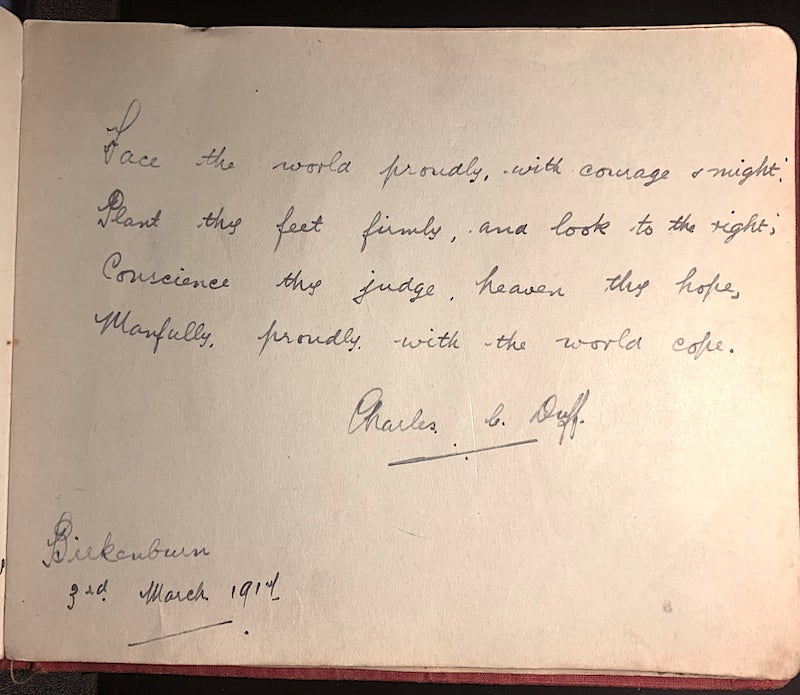

Dunkeld is a small village which sits on the banks of the River Tay, Perth, and according to the 1911 census, the population numbered just 798 people.3 Other entries from Dunkeld give a small insight into Mary's world. She was friends with the Seatons (Isabella and Jane), who lived at Ladywell Cottage along with a Charlotte J. Millar. She was also friends with the Duffs, who lived at Birkenburn.

Charles C Duff (figure 5), a Private in 4/5th (Angus and Dundee) Battalion, Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) died from wounds on 3 September 1918. His brother William S, who was with the 7th Battalion (The Buffs) East Kent Regiment, was killed the month before. Mary’s own brother Duncan, having transferred to the 37th Machine gun Corp, died a month before that aged just 26. Charles, William and Duncan all attended Dunkeld Royal Higher Grade School, and their names are all remembered on the school’s war memorial.

The main war memorial for Dunkeld contains 74 names — given the size of the town, and presuming a 50/50 male female split, 19% or 1 in 5 men in Dunkeld gave their life.

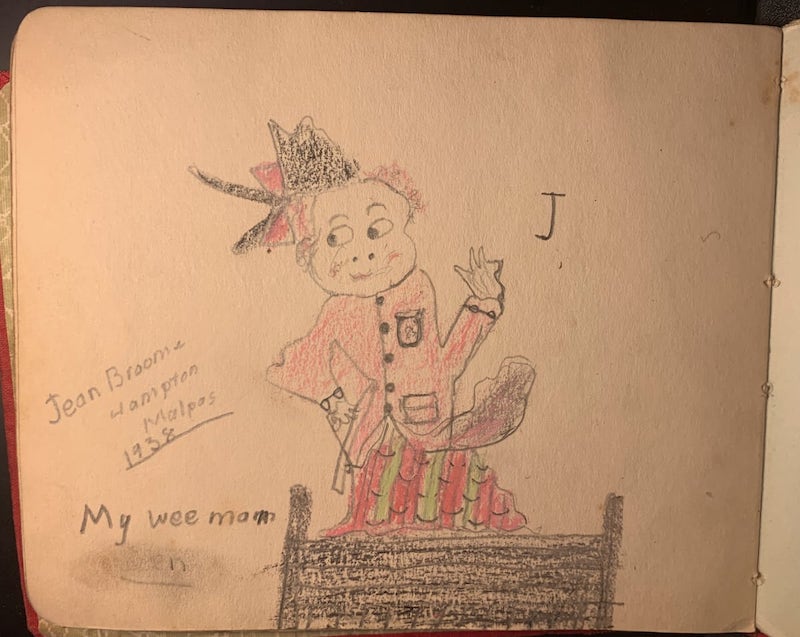

Returning to Mary, the book provides another clue as to her identity thanks to a graffiti artist.

A Jean Broome took her pencils to the book in the late 1930s, mainly copying the existing entries, as well as adding some butterflies here and there — I bear her no ill, as I have a memory, as a child, of being given an old book by a relative to colour in to 'shut us up'. This is important as Mary Ann Murray married a Leonard George Broome (1884-1962) in 1923 (the 1911 census has his occupation as an Estate Labourer in Cheshire), and it looks like they spent the rest of their lives in the area, with Jean Broome being born in 1928.4 I believe it is therefore conclusive that this was her book.

The Scotsman from December 1915 provides further information about Mary. In the classified section there is a reference, from a Mrs Steuart Fothringham, of Fothringham Hill House, Angus, who recommends Mary Murray of Upper Hatton as a Housemaid.5

Hampton Hall Malpas

Malpas, 200 miles south of Dunkeld as the crow flies, is a small market town in Cheshire with a population, according to the 2021 census, of just 2,314. The 1921 census put the population one hundred years earlier at just half that, at 1,098.

Hampton Hall is an ambiguous identifier as there were two halls in Malpas with the same name, both occupied by the same family: the Wilding Joneses. The first (New Hall), built in 1872, overlooked the Dee Valley and was the home of Wilding Wilding Jones (1832-1919) who married Catherine Murray, from Edinburgh, in 1863. The second (Old Hall), was a much older wooden timber property on the precincts of the estate occupied by his son Charles Wilding Jones (1864-1949) who married Florence Burton, from Cliburn, in 1898.6 They were not small houses; an article in the Chester Courant, on the New Hall's opening in 1874, describes it as being 'designed in an Elizabethan style of architecture, of pressed red pressed bricks and stone dressings throughout, with ornamental worked gables and roofs covered with red ornamental tiles'. The article further states that there were upwards of 30 guests comfortably seated in the dining hall.7 The New Hall was sold for demolition (due to changes in the tax laws) in 1950 and an article, interviewing then owner C.L. Wilder Jones, mentions that it had 20 bedrooms and sat on a 240-acre estate.8

In comparison, an advert in Country Life from 1925 describes the Old Hall as consisting of 16 bedrooms and dressing rooms, nursery suite, bathroom, four reception rooms, sitting in 8 acres (available to rent fully-furnished at the nominal rent of £200 per annum).9

In addition, the Wilding Joneses were landed gentry and there was Hampton Hall Farm, which, again, is ambiguous. The impression given by looking at some auction reports and news articles of the period is that 'Hampton Hall Farm' was both a dairy farm overseen by Charles Wilding Jones as well as the collective name for several tenanted smaller farms and small holdings on the estate — however, it is outside my area of knowledge and, based on the evidence I have, I cannot say much with any authority.

Both houses employed staff and, according to recruitment adverts of the period, Old Hall employed nine; it seems both Wilding Joneses went through chauffeurs at some rate (paid £1 a week to live in and to double up as a groom) — the reason for this may very well be due to conscription. From other adverts, it looks like the houses further employed a Cook, Housemaids (Upper £26, Lower £18 a year), and a Butler (£50 a year).10

It is interesting to note that these adverts all appeared in the Scotsman newspaper. Given the reference to Mary as a Housemaid, it seems only logical to assume she left Dunkeld to go and work for the Wilding Joneses at one of the Hampton Halls.

Where it gets weird

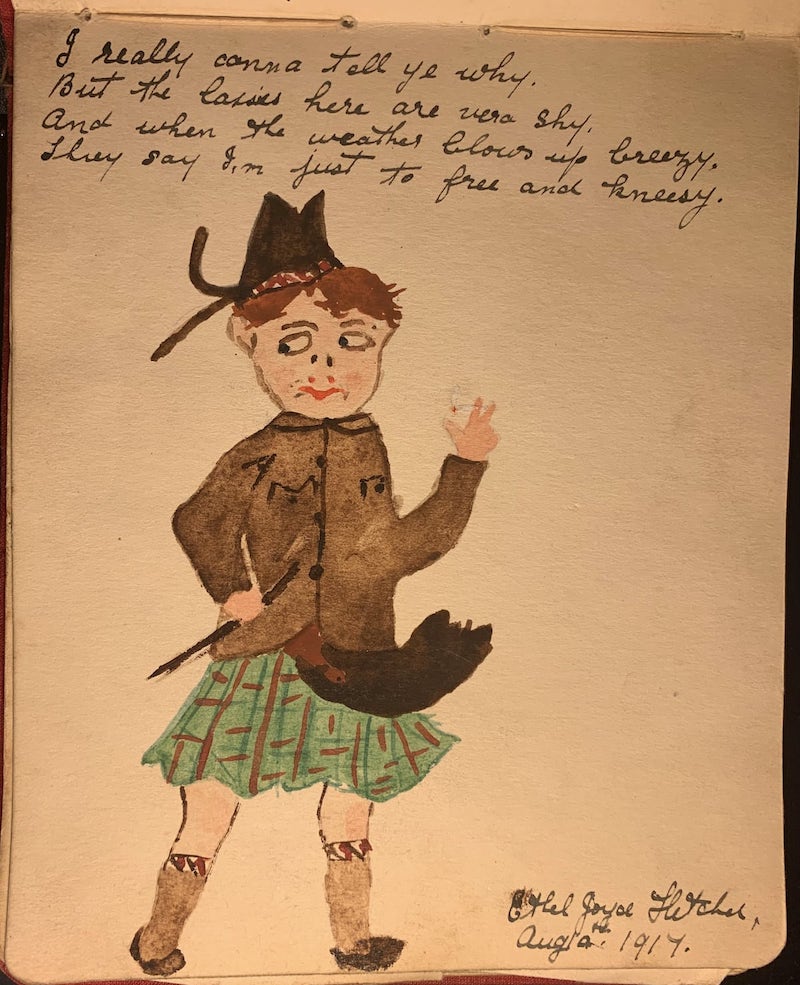

It therefore follows, and a reasonable assumption suggests, that this is a 'below stairs' book — but of the people identified in the book, I can only find one other name, and it's a stretch, who worked in domestic service. That is an Ethel Joyce Fletcher (1900-1987) who coincidentally had one of her entries copied by our graffiti artist — which in turn is a copy of a postcard. I say that this identification is a stretch as it comes from her obituary, which mentions she had been a housekeeper. 11

Most of the entries by women in the book all seem to come from working class families — such as the aforementioned Florence Rutter, whose father was a fisherman. Another reason for steering it away from 'below stairs' is that I have in my collection a book that I believe to be an example of a below stairs book, and what stands out is where the signatures include a from, it is the name of another large property/estate. In the book under scrutiny, all the 'from' entries are from inconspicuous, ordinary, everyday homes.

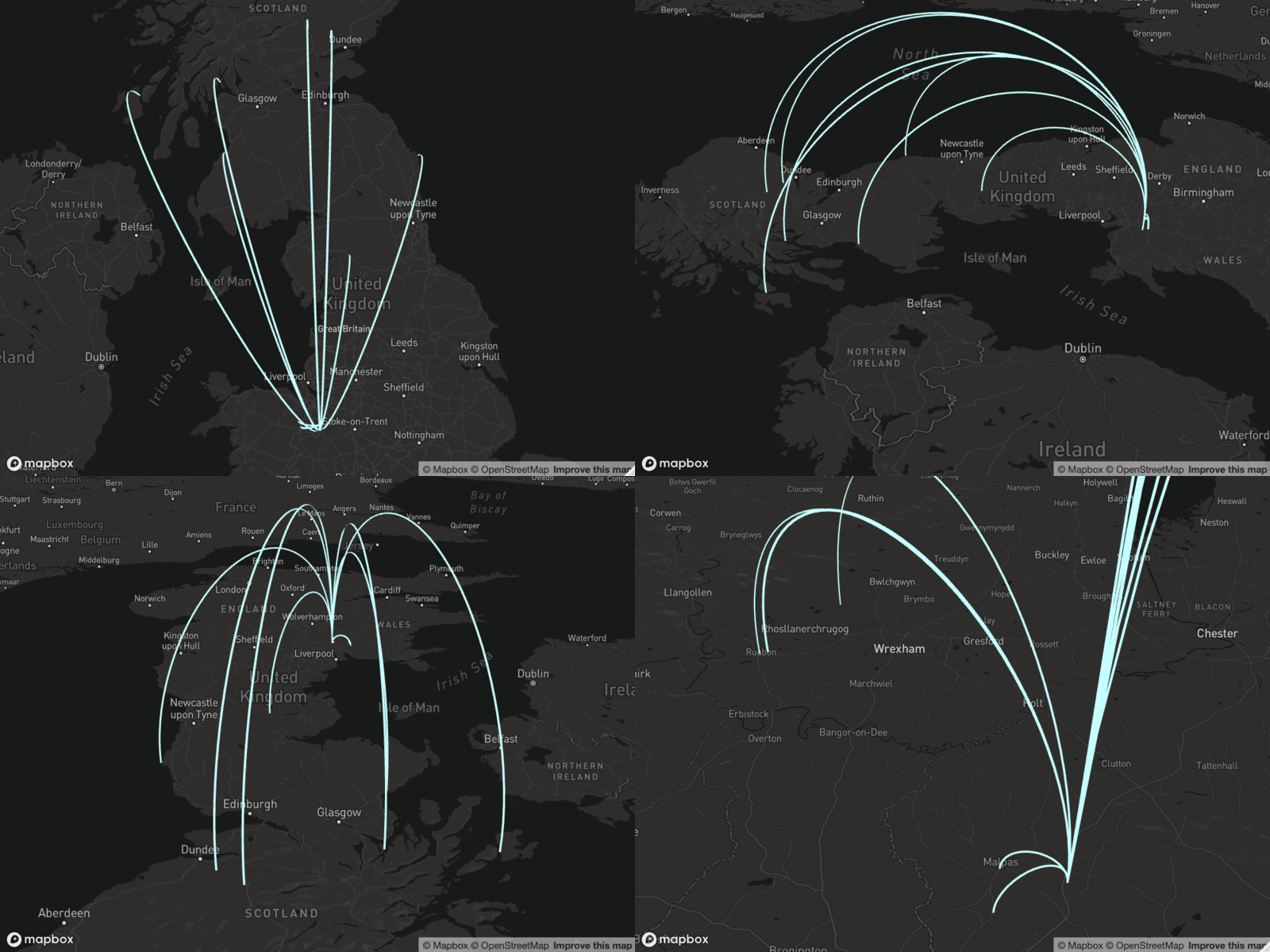

Taking a closer look at the format of the entries, I presume that if I were to go somewhere for a long time or was local to the book owners and/or good friends I would just sign my name. But, if I was only going to be somewhere temporarily, or meeting someone for the first time, I would include my full address. Based on that assumption, I decided to take all the entries that matched this format and plot them on a map which resulted in more mystery.

The first thing to strike me is the distances involved — the furthest, as the crow flies, is an entry from Euphemia McDougall, who lived at Heather House, Port Askaig, on the Isle of Islay — a distance of 301 miles. The high number of entries originating from southern Scotland was also of note and supports the idea of recruitment of household staff from Scotland.12 But then there are entries from all over the place — including Malpas itself — and many are from rural places — such as an entry by Myfawny Roberts, from Brynn Tyford, Wales.

This all begs the question: why were all these people descending upon Hampton Hall?

While Malpas is too small to warrant a direct mention, there are numerous references to the Land Army in Cheshire — including references to a training centre being set up in the area. According to a government report dated 3 April 1918, as well as female volunteers, soldier labour was also employed — those recovering from injuries and those who could be spared (the document notes some 40,000 were employed in this manner by this date), which would explain entries in the book from those in the services that were not injured — such as an example from 1st Air Mechanic Walter George Gill. In addition, the report also mentions the use of local and nearby labour (explaining the pattern on the map above), as well as the use of Prisoners of War and Interned Aliens — there are a few pages in the autograph book that contain only signatures, some of which contain accented and umlauted characters as in the example in Figure 9.13

However, just as there is no evidence for Hampton Hall being used in a convalescent setting there is no direct evidence — that I could find — to tie the book to the Land Army, nor is there a strong enough thread to tie it to domestic service — perhaps it is a mixture of all three? Regardless, there does seem to be a happy story behind it. Mary travelled down from Dunkeld, met a wide mixture of people, fell in love, stayed in the area, married and had a child.

The Entries

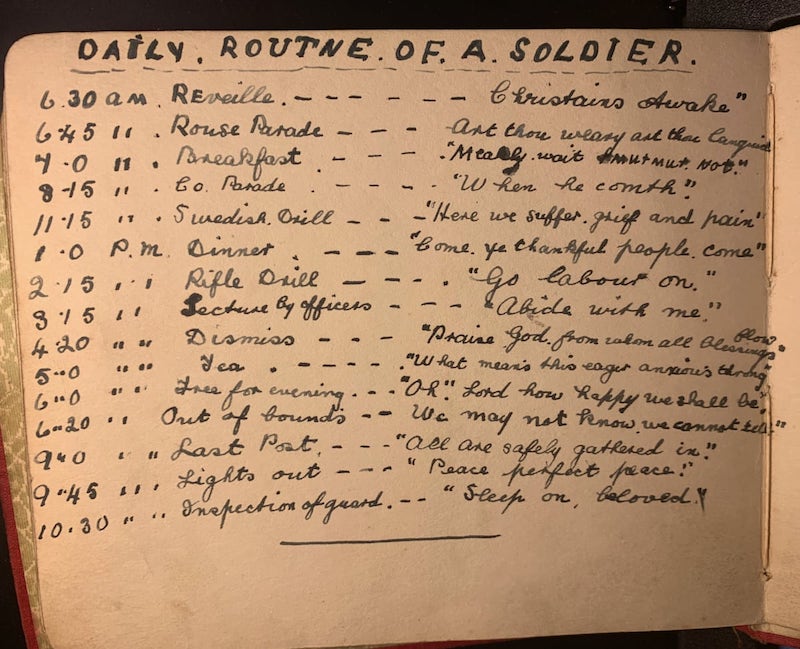

For now, having mentioned quite a few entries above, I am just going to pick out one further example, seen in Figure 10. This is undated and the creator is unknown, but it is important for the following reason: it is an example of trench culture flowing back from the front into civilian culture — this first appeared in the trench journal the Command Gazette, in 1916, and was copied by several other journals including the Canadian Maple Leaf.14

Language

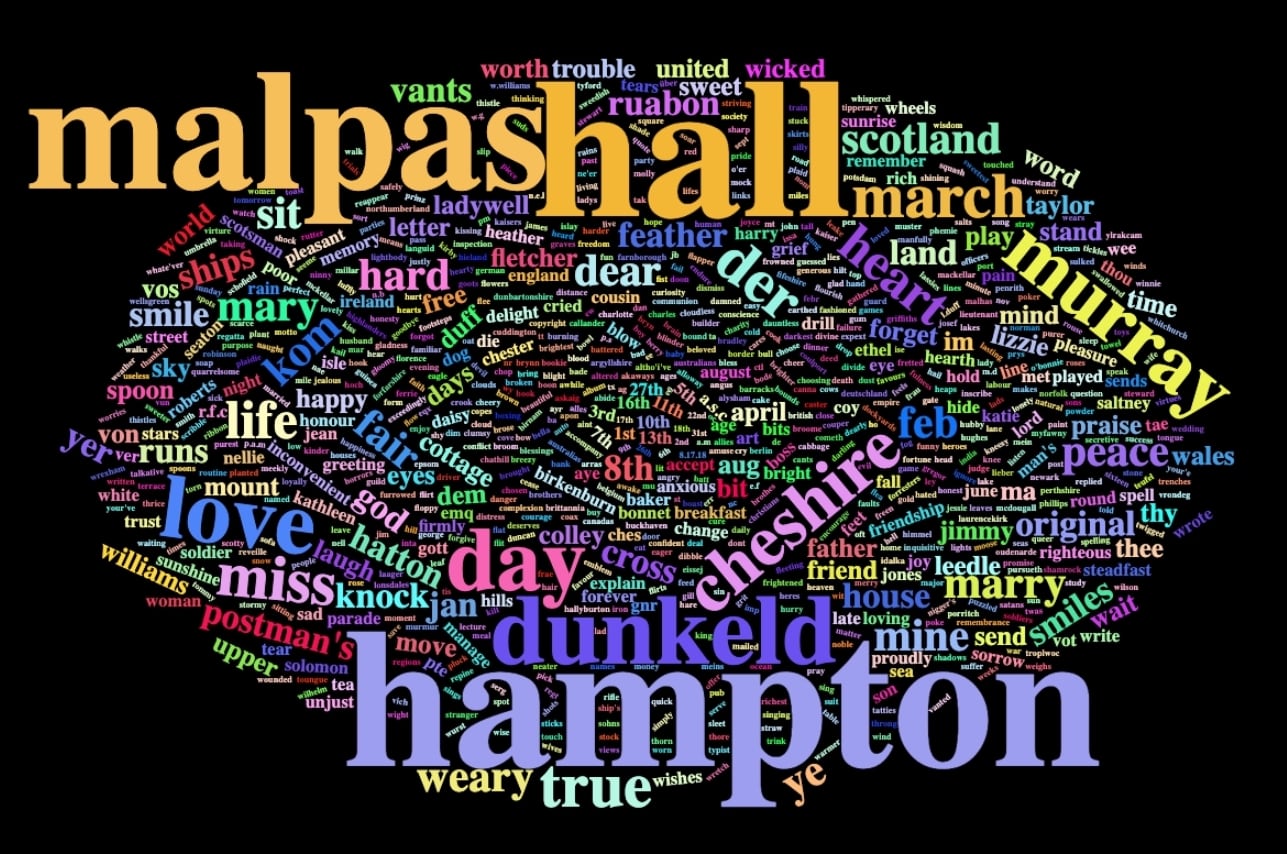

I mentioned in the first entry that language is something I want to track, and while it is still early days, what is interesting in the case of the Hampton Hall book is that there is a clear signature with a dominance of places, names and dates. The lexicon is also a lot larger compared to Jennie Clegg’s Book, with 892 words (vs 475) and I am wondering how much of that is being driven by regionality?

As before, all the entries can be found here and are shared under a creative commons licence. The entries for Hampton Hall can be found in the folder ‘HAMPTON - CHESHIRE-270223’. There is a text document and photograph for each entry. A spreadsheet called MasterRecord, in the root directory, contains the meta-data.

The Technical Bit

Behind sharing my ephemera collection, I am also plotting these entries onto a matrix to see what insights can be gained. This is a very much a work-in-progress and the following are some notes on the process — which may be of limited interest.

From a technical viewpoint, part of the reason for choosing this book next was the volume of entries. In terms of building the matrix I wanted to get a good feel, as the matrix expands, for what sorts of problems might come up — which were quite a few. Two immediate problems: the first was where there are entries from the same family — I need a way of recording this information in the metadata which is scalable. The second is where an entry has more than one influence behind it, i.e. the contributor has used part of a song and a poem — this is a minor issue as a there are a number of options to hand; it depends on how the matrix develops as to which one is the more suitable.

A few further minor issues: the graffiti artist presents an interesting challenge, and I am not sure about the best way of recording their entries — they are certainly not the only 'vandal' in my collection. As in the previous entry in this series, the matrix column headings are very much a work in progress.

Another reason for choosing this book was that, while the spine was broken, I wouldn't call the book fragile. I wanted to test a few different ways of photographing the book — lighting seems to be the biggest problem, and a few pages need to be redone, but I will write more on this in a later entry as many of the other issues from the test have since been overcome.

The map presents some bigger challenges. The map presented in Figure 8 only contained entries where they fitted the '@Hampton Hall, Malpas / content / by / from' format. Figure 12 shows entries from the book that had the 'from' element, but not necessarily anything else. It would be good to be able to show them on the same map and clearly differentiate between the two.

The second issue is that, for the map in Figure 8, I used the RStudio package mapdeck which in turn uses mapbox. To do so requires the generation of a software key — as I am sharing this, I need to remove the key each time I upload it to Github, which is something I want to avoid (or I'm open to a suggestion of a way of managing this?).

The map in Figure 12 (which should be interactive) has been produced using the leaflet package, which does not require a specific key, but does not appear to offer a way of creating the nice lines joining the dots as in Figure 8. Finally, neither map approach seems to offer an obvious way to account for the scenario where two or more entries could originate from the same place on different dates.

As my focus on this project is to examine what ephemera can offer in the way of historical evidence, I feel being able to map the books' entries is important, and therefore it is something I will continue to develop — for anyone interested, there are two scripts in the project starting with the prefix 'Mapping' that cover Figures 8 and 11.

I've also added a small handful of scripts starting with the prefix PDQ. These are mainly to produce lists — such as a list of all the names behind the entries.

-

Service record. ↩︎

-

Chester Chronicle, 26 June 1915, p.6; https://vad.redcross.org.uk/record?rowKey=121504, retrieved 10 May 2023. ↩︎

-

1901 Census England and Wales. ↩︎

-

1901 Census England and Wales. ↩︎

-

The Scotsman, 1 December 1915, p.2. ↩︎

-

Cheshire Observer, 15 November 1919, p.11; Globe, 27 January 1898, p.7. ↩︎

-

Chester Courant, 23 September 1874, p.5. ↩︎

-

Nantwich Chronicle, 2 September 1950, p.6. ↩︎

-

Country Life, 28 March 1925, p.xx. ↩︎

-

The Scotsman, 12 June 1916, p.3; The Scotsman, 22 March 1916, p.3; The Scotsman, 28 June 1916, p.3. ↩︎

-

The Chronicle, 26 June 1987, p.24. ↩︎

-

Scotland economy shrank by 11% in the early months of the war due to a contraction in heavy industries; Derek R. Young, ‘Voluntary Recruitment in Scotland,1914-1916’ (Ph D, University of Glasgow, 2001),p.385. ↩︎

-

TNA/GT.4141, Board of Agriculture and Fisheries, Food Production Department Report, 3 April 1918, pp.74-79. ↩︎

-

The Command Gazette, 2nd February 1916, p.2; The Remount Herald, 28 April 1916, p.6; The Searchlight, 1 September 1916, p.204; The Maple Leaf: The Magazine of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1 April 1917, p.57; The "Bombshell": The Official Organ of the N.P.F, 1 November 1918, p.14. ↩︎